Part III-Jakob Hutter’s Arrest and Execution

- Clint Stahl

- Jan 24, 2013

- 4 min read

Jakob Hutter was arrested in November of 1535 in the town of Klausen in South Tyrol. In Klausen we visited the town museum to learn about the details surrounding Jakob Hutter’s arrest and imprisonment in the Branzoll Castle towering above the town. The museum director, Christoph Gasser, showed us an old town register documenting important civic meetings and the annual assignment of positions in the town dating back to the early 1500s. We were interested in tracing the position of the sextant, because from our Chronicles we know that Jakob Hutter was given refuge in Klausen by a sextant by the name of Jacob Stainer. The archivist’s mannerisms, choice of words and personality made him a congenial and interesting person to visit with.

The records showed that Jakob Stainer was assigned the job of sextant and reinstated for several consecutive years, before being stripped of his job because of his Anabaptist sympathies. Jakob Stainer became attracted to the Anabaptist teachings and his house eventually became a favourite place for traveling evangelists such as Jakob Hutter. Jakob Stainer had built his house on the opposite side of the Inn River across from the church where he served as sextant, indicating his significant wealth and influence. Because the house was built across the river, separate from the village of Klausen, it belonged to a different political and legal jurisdiction than the village territory, and hence, was a perfect place to stay for people hiding from the authorities, including Anabaptists.

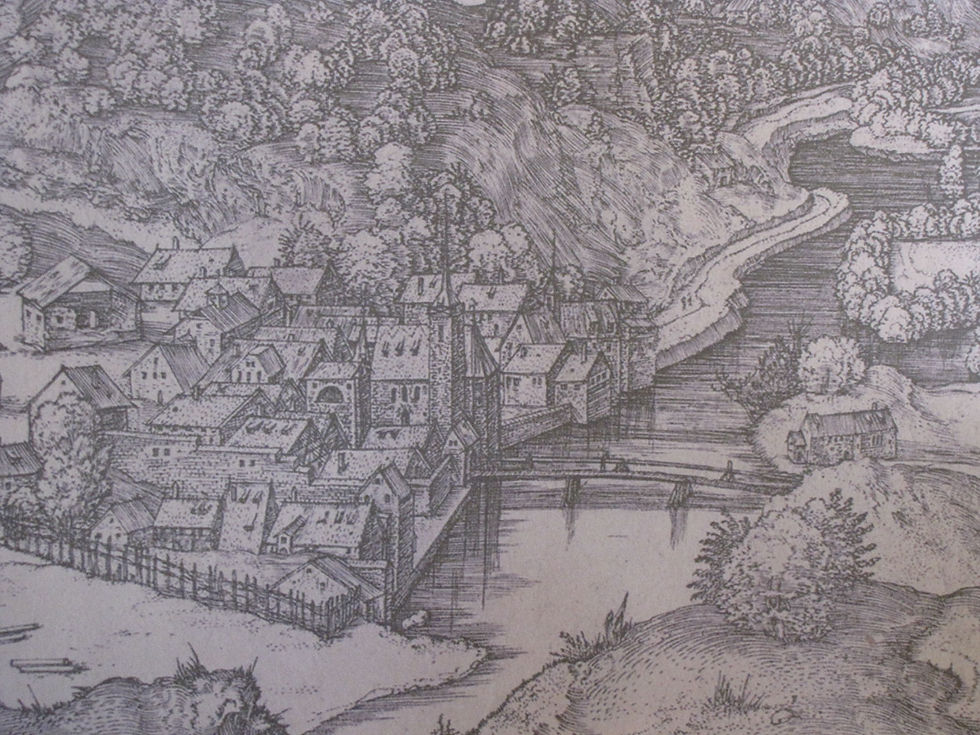

The woodcut artist Albrecht Dürer once visited Klausen and produced a piece featuring the village. Interestingly, the woodcut image clearly shows the home of Jakob Stainer across the river. It is in this home that Jakob Hutter was arrested after the bishop of Klausen made a deal with the local ruler to hand him over to his jurisdiction for imprisonment in the secure Branzoll Castle.

A woodcut by Albrecht Dürer featuring the town of Klausen and the home where Jakob and Katherina Hutter were arrested.

Hutter’s wife, Katherine, was also apprehended, but she was placed in a less secure castle near Gufidaun. During her imprisonment she gave birth to her firstborn child, which was presumably seized by the authorities. We do not know if it was a boy or a girl or whether the child survived. Katherine later managed to escape without her child. Two years later she was caught and drowned for her faith at Schöneck Castle in the Puster Valley.

Branzoll Castle, the place where Jakob Hutter was held before being taken to Innsbruck to his death, sits commandingly above the town of Klausen. Two-thirds of the castle was destroyed in a fire, but several castle enthusiasts restored the remaining part and today a friendly lady, along with her son and daughter-in-law, inhabits the castle. Before showing us inside, the homeowner served us a refreshing glass of elderberry juice and delicious raspberry squares and shared stories about the castle’s history.

Our first impression upon seeing that the castle tower was inhabited was, “Wow, that looks like an interesting place to live!” Interesting, yes. But, practically speaking, a castle is not an ideal place to live. For one, it is difficult to heat and cool in a predictable and controlled manner because of its thick walls. Getting from the castle to the town a stone’s throw below takes awhile by car. As a shortcut, one can take the steps instead, but there are over one hundred of them! Modifications to the building have to be passed by the government. The windows are small, giving the building a dark and gloomy atmosphere. Only somebody who truly loves the place would be willing to live here.

From Klausen, Jakob Hutter was brought to Innsbruck to face the wrath and grim justice of Emperor Ferdinand I, who saw it as his personal mission to root out Anabaptism in his Catholic territories. From Moravia, Jakob Hutter had written some pretty sharp words against the Emperor, calling him the Anti-Christ and strongly criticizing the emperor’s role in harassing a group of nonviolent followers of Christ with such heavy-handed measures.

Before his execution in Innsbruck, Hutter was forced to look at what he called idols—the elaborate statues of the saints, altars and paintings in St. Jakob’s parish church (now a cathedral) near the town square. When we visited the church courtyard at about 10:00 Sunday morning, worship was in progress and we could only briefly enter the building. The sermon could be heard outside, thanks to an amplification system. Somehow, it seemed fitting that we could not stay long in the building that Hutter was marched through as a final act of humiliation, although we could hear words of Scripture read which he would have found moving as well.

The text was from John, Chapter 10, 1-4: “Very truly, I tell you, anyone who does not enter the sheepfold by the gate but climbs in by another way is a thief and a bandit. The one who enters by the gate is the shepherd of the sheep. The gatekeeper opens the gate for him, and the sheep hear his voice. He calls his own sheep by name and leads them out. When he has brought out all his own, he goes ahead of them, and the sheep follow him because they know his voice” (NRSV). Following the shepherd’s voice, Jakob Hutter knew, did not mean enjoying green pastures in this life. Discipleship demanded a costly sacrifice and he was prepared to make it, through the gift of God’s Spirit.

While in Innsbruck, Hutter was held in the Kräuterturm[1] in the northwestern corner of the city. The authorities tortured him to force him to reveal the names of his brothers, sisters and supporters, but he refused to betray anybody.

While King Ferdinand I may have looked on under the famous golden roof das Goldene Dachl of his court in Innsbruck, Jakob Hutter was publicly burned at the stake. His public execution was to serve as an example to the common people of the consequences of embracing the heretical faith.

In the fourth and final post, we will explore a plan to build a Hutterpark next to the Inn River in Innsbruck.

[1] Kräuterturm comes from the word chraut in the local dialect meaning “gun powder.” Apparently the buildings nearby were used to store gunpowder at one time. Astrid von Schlachta, Verbrannte Visionen, 112. An alternate meaning of the word “Kräuter” is herbs; it is a possibility that the buildings stored herbs used in distilling spirits.

Comments